47 Parks

47 Parks

Guest Post by Kate (a genuine outdoor explorer)

Kate and I have known each other for quite a few years. We both share a love of the outdoors and an appreciation of true solitude that can only be found in wild places. At the same time, Kate and I have an appreciation for outdoor recreation that requires a team. We recognize the joy in both individual effort and collaboration. This is Kate’s incredible story.

Deep Places: A Novice Canyoneer’s Experiences in Zion National Park

Zion National Park tends to make an impression on people. My first impression of many came from inside the car just as we emerged with a line of tourist traffic from one of Zion’s several long tunnels carved out from the rock. I was in the passenger’s seat which permitted me to rubberneck, and I craned to look as far as I could underneath the bridge we were crossing. Beneath us, waves of pale sandstone were sinking into the earth. A sinuous, deepening void had carved itself into the rock.

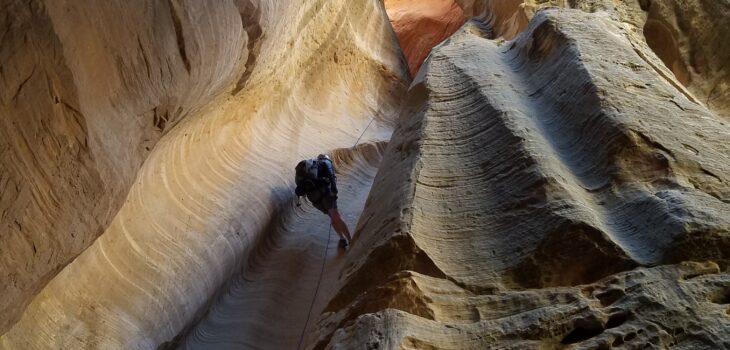

That void is called Pine Creek Canyon, and in just a few hours we would be standing at its sandy entrance where the sun already struggled to reach deep enough to warm the air, and we’d be rigging into our ropes and following the swoops in the sandstone down, each wave going deeper than the last, until finally we were well and truly underground.

It felt like a secret place. I stood in the sand in my wet tennis shoes in disbelief. Above, the cars of other tourists rumbled continuously over the bridge. It is a strange thing to park in a bustling tourist parking lot on a bright fall day, surrounded by people in sun hats and flip flops, and suit up in your wetsuit and layers upon layers of climbing gear — harnesses with carabiners clinking from their loops, backups of everything—two ATCs, two personal anchors; coils and coils of rope looped around your shoulders or stuffed into whatever ramshackle backpack you’d selected for sacrifice to the abrasive sandstone. Topped off with my bright orange climbing helmet. I felt like a space woman walking among martians. Fellow tourists gave us sly glances and watched our progress down the approach to Pine Creek Canyon. Some of them would follow us down the path and stand at the entrance to the void, although they would go no further.

Since moving to Colorado, I have been lucky enough to fall in with a group that makes a once-a-year excursion to Zion for technical class 3 canyoneering. It is a whirlwind three days and three nights bookended by two 10-hour overnight drives (with work the next day!), full of ludicrously early rises from a terrible RV campground, shivery evening returns to camp, and many descents on the strand of a rope into some questionable places.

But it’s all worth it, because each canyon has its own, otherworldly magic to it:

There is a rating system to canyoneering that I am still getting the hang of. Not simple and clean like climbing ratings (what’s more straightforward than “5.11B+”?), canyoneering ratings are a jumble of numbers and letters and shapes. They describe the technical skills required, the presence of absence of water and whether or not it’s flowing, the time it might take for an average-sized and -skilled crew to pass through it, and—quantified in number of stars—the recommended level of stoke.

Pine Creek is rated 3BII(and 5 stars) meaning that technical rope and rappelling skills are required, water is present but unmoving, it takes a few hours or half a day to move through, and demands highest possible stoke. My group stays more or less within this classification. There are harder classifications out there. I’ve been warned about them. They can require rappelling into deep natural wells and dragging yourself out with hooks, or boosting your partner up high enough that they can climb up and pull you out, or increasingly drastic measures. There are anchors made of a few sticks wedged between rocks and rappels into powerful waterfalls. There are mandatory downclimbs (descents without a rope) where a wrong move means serious injury or death in one of Zion’s remotest places. We’ll leave those to the professionals, I suppose, for now. Our class 3 canyons offer more than enough adventure.

In the two (and counting) years I’ve been lucky enough to attend this trip, I’ve racked up a handy collection of canyons to check off my list:

- Keyhole (3BI (4 stars))

- Pine Creek (3BII (5 stars))

- Telephone (3AIII (3 stars))

- Mystery Canyon (3BIII (5 stars))

- Spry Canyon (3A/BIII (3 stars))

- Birch Hollow (3AIII (3 stars))

Despite its 5-star rating, I don’t remember very much from Pine Creek. We’d spent the first few hours of the morning in a wet canyon called Keyhole. Keyhole is a narrow, twisting, wetsuit-strongly-recommended classic with aesthetic sandstone sweeping up and under you. Many of the rappels drop you straight into dubious pools whose waters are so murky you can’t see through to the bottom. I was warned about possible casualties in these pools—one year before my time my crew had come face to face with a departed sheep bobbing rancidly in the pool below the first rappel. I waded through the waters with my feet sinking in and then breaking out from obscure mud, the bones of lost sheep surely just inches away from my tennis shoes.

By the time we’d made it through the last of the twists and turns of Keyhole and hiked down its sandy wash back to the road, a chill had set in that even the blazing midmorning sun couldn’t dispel from inside my layer of ill-fitting neoprene. As I stood at the entrance to Pine Creek, already shivering, I knew the next few hours would offer me little mercy.

I remember the pale blue light that made its way in, a sort of twilight with a rim of real sunlight visible on the sandstone far overhead. I remember standing on the ledge in between two rappels thinking I’d better stop to take this in, it was so hauntingly beautiful. I was in a strange new world of verticality. Below me I could see only darkness and the rope pointing down into it in a straight line, taut with my friend’s weight. It was a narrow twilight world not quite underground but in between two massive slabs of split-open earth.

I clipped into the rappel once it had gone slack again and thought I’d better double, triple, quadruple check my setup. Most rope accidents happen in just these sorts of situations, when overconfidence, carelessness, or mind-dulling cold can cause a person to think the rope will catch them when it won’t.

I quadruple-checked and braced my feet on the edge of the rocks and swung myself out over nothing, both hands on the rope. It was a posture I would learn well over dozens of rappels, and one which requires a certain amount of faith. Sometimes the anchors are at strange angles or the rocks drop away too quickly, before you can get the rope settled to take your weight. You have to be careful not to slam your shins or crush your fingers or worse, sever the rope on some sharp edge of rock.

Not all of Zion’s canyons are close-walled and serpentine. In some of them, you rig in to your rappels on the edges of wide cliffs with stunning wideshot views of Zion’s roiling oranges and whites behind you.

One of the scariest rappels for me happened on the edge of just one such cliff above Mystery Springs. I knew this was one of Mystery’s longest drops at over 100 feet, and to get out to the anchor I had to traverse an unprotected, 4- or 5-foot wide sloping ledge above the drop. This was the second most intimidating part of Mystery for me. I stepped carefully to ensure I only stepped on solid rock instead of gravel or debris, hugging the wall, and when I finally came to the anchor and clipped in my sense of relief was minimal—I still had to make the long rappel. I checked, double-checked, quadruple-checked my setup and leaned out over nothing, letting my weight sink into the rope, and all anxiety fell away.

Mystery Canyon also contained the most triumphant rappel for me (which was also the first most intimidating part).

Many of you may have heard of the Narrows Hike down the Virgin River, one of the most famous hikes in the world. Every year thousands of people suit up with canyoneering boots and walking sticks to slog up and down the Virgin’s riverbed with orange canyon walls towering above. The last rappel in Mystery Canyon is a wet, sloping, algae-slicked 110 foot cascade down one of those walls into the Virgin Narrows.

I could hear the crowds before I saw them—throngs of people struggling up or down the chunky riverbed, calling out to each other and laughing. They looked like marching ants from our high vantage point. I sat (or hid, if you prefer) out of sight behind a ledge while we dropped our rope. The moment it landed a crowd gathered. I’d been warned about this drop—I would have to brace my feet against the slippery vegetated walls and I was going to have to do it with an audience, all of whom (I imagined) were just waiting for my feet to shoot out from under me and my face to smash straight into the rock. My heart pounded when it was my turn to do the descent. I clipped in (quadruple checking) and backed myself out over the edge, not looking, but keenly aware of the many eyes upon me. I tried to project an attitude of confidence and finesse as I let pressure off the brake side of the rope, allowing it to start to slide through my ATC.

It was a long 110 feet, but my face and the canyon wall remained blessedly separate.

Cheers broke out as soon as my feet touched the bottom. I don’t know why this is, but I guess all that fake confidence and finesse really came through for me. Either that or everyone saw how nervous I was and wanted me to know how well they felt I’d done, given the circumstances. I went and joined the rest of my party members still without looking at the crowd. A man came up to me and asked me for my picture, no explanation given. I declined. If I never get another 15 minutes of fame, this one will be enough!

Canyoneering is not my main outdoor sport, or even one I partake in particularly often. I am a tourist to Zion and to canyoneering, in every sense of the word. But I’m incredibly grateful to have had these experiences, even the ones that didn’t make the cut in this post: the enraged yellowjackets that plagued us all through Telephone, as well as Telephone’s dubious anchors made of logs and piles of rocks, the antagonistic rope-bag gatekeepers (a rival canyoneering gang, if such things can be said to exist) who angrily confronted us on our ragtag gear on the hike out of the Narrows, the many sketchy down climbs, the grueling hikes either up to or out from the canyons (shuttles are for posers, apparently), the many pathfinding difficulties, the Type-2 fun (and Type-1 fun!), the incredible camaraderie and teamwork of our tight-knit crew as we navigated all of this, and the countless in-between moments of casual, breathtaking beauty, when I had to pinch myself to remember to take it all in.

I hope you liked this hodgepodge of canyoneering stories. I’ve always found the deep, dark places in the world the most compelling to explore, and maybe you do, too! If not, please enjoy this picture of a passed-out shop kitten in Springdale. Until next time!

Read a previous post about Zion’s significance in my (Steph’s) life.